When Mike Wooding died in Meregill Skit on 9th August 2006 from natural causes at the age of 63, the caving community lost one of its most prominent members.

Mike's caving career spanned over forty years, and his exploits made him a legend in his own lifetime. He was a pioneer of modern cave diving, and was involved in significant explorations in Mendip, South Wales and Yorkshire, undertaking hard exploration trips to the very end of his life.

Mike started caving whilst he was at Bristol University reading Engineering. He had previously been heavily into climbing, and was responsible for several new routes in Cheddar Gorge, but in 1963 he turned to caving, soon teaming up with Dave Drew and Dave Savage. No casual tourist trips for them - their objectives were to push Swildon's Hole and Stoke Lane Slocker to their conclusions, and to do so required diving. At this stage the Cave Diving Group was quiescent, so the three taught themselves to dive and set up the rather grandiosely named Independent Cave Diving Group.

This select little group was only active for a few months, but they took the Mendip caving scene by storm, making significant progress in their chosen objectives, and elsewhere. Mike rapidly established a reputation for being someone special to the extent that he was being described by Peter Johnson in "The History of Mendip Caving" as "the legendary Mike Wooding" within four years of him entering the sport. One trip that stands out from that period is a solo trip during which he passed both the Swildon's 7 and Swildon's 8 sumps, to reach the Swildon's 9 sump.

Mike came in from the cold and helped to re-energise the Cave Diving Group, for which he became secretary of the Mendip Section. Unfortunately, he had a serious falling out with Oliver Lloyd, and thereafter, whilst happy to cave and cooperate with anyone, he avoided joining another club. Following this episode, he left Mendip and moved up the Dales where he found fresh pastures. He was, however, made an Honary Life Member of the CDG at the group's 50th anniversary celebrations in 1996 - an accolade of which he was very proud.

In 1970 he started at Lancaster University from which he graduated with a degree in computer science, and in 1979 he married June Mitton, and together they converted a derelict barn into a home, in which they raised their daughter Hazel and an assortment of dogs, horses, and goats.

In Yorkshire caving circles Mike will be especially remembered for his explorations in the Gaping Gill system, and for his Keld Head dive. He became involved with Gaping Gill in 1970 when working with Sid Perou on the BBC film "The Lost River of Gaping Gill". Diving upstream in Ingleborough Cave, he succeeded in passing two sumps totalling 200 m in length, and entered Gandalf's Gallery - 220 m of high level passages.

A year later, he ventured in Gaping Gill's Far Country on a solo trip, and moving a boulder in Clay Cavern at the far end of the system he exposed a body-sized tube which led to a 3 m drop, and hence into the lower series of Far Waters. On a subsequent solo trip during which he discovered and climbed Hallucination Aven at the end of the new series, he returned to Bar Pot to discover the ladder he had used on the entrance pitch had been removed. Undaunted, he free-climbed out.

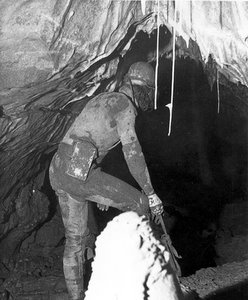

Mike's Keld Head dive in 1970 was a deliberate attempt to effectively break the equivalent of cave diving's four minute mile. He firmly believed that the only barriers to long underwater explorations were psychological, and he set out to overcome such barriers once and for all. He penetrated what at that time was an incredible 1,100' into the system during a dive that lasted some 51 minutes.

Mike made three important contributions to cave diving. Firstly, he entered the sport when air was taking over from oxygen, and in spite of the ICDG's somewhat cavalier approach, he became deeply concerned with improving the effectiveness and safety of the equipment, enlisting his engineering discipline to overcome the various challenges.

Secondly, sumps were then seen as an obstacle - something that had to be passed to get to the next section of "proper" cave. Mike saw sumps as something to be explored in their own right. When he made his dive in Keld Head he was not expecting to find open passage - he simply wanted to explore the underwater system that lay behind the entrance pool. This dive changed the mindset of those that followed, and laid the way for the explorations of such as the Keld Head and Chaple-le-Dale phreatic systems by others.

Thirdly, and possibly most importantly, Mike inspired future generations not only by his example and his exploits, but by his willingness to provide help and encouragement to others. The following generations of cave divers have been only too happy to acknowledge their debt to him.

In the early 1970s, Mike had a bad motorbike accident, and thereafter had to live with various health problems, including ME. He was lost to caving for a while partly due to his health and partly due to domestic responsibilities, but he took up running in the mid-1980s which he approached with the same commitment and enthusiasm as he did everything else. At first he concentrated on road-racing, running several marathons, but he found his true vocation in long-distance fell-running events. He was a regular competitor in the Fellsman, an annual 61 mile long race which ascends 11,000'. He last completed it three months before he died, with a time of a little over 19 hours.

At the end of 2002, Mike's wife June died after a long illness, and a few months later he reappeared on the caving scene. During the next three years he was involved in a six month solo effort P-bolting a magnificent route down Rathole in Gaping Gill; opening up Small Mammal Pot - a new entrance into the Gaping Gill system; and climbing a 33 m aven at the end of Avalanche Pot Inlet in Gaping Gill. At the same time, he familiarized himself with modern cave diving techniques, and embarked on a project digging the underwater choke at the end of Meregill Skit, in which he was to lose his life.

Mike also went on a number of international expeditions over the years. In 1966 he was a member of the infamous Ken Pearce expedition to the Berger, but personalities clashed and he was unceremoniously thrown out of the expedition. In the early 1970s he was a member of a successful Pierre St. Martin expedition, and on a Berger expedition in 1986 he spent a couple of days bolting the 205 m pitch in the la Scialet de la Fromagère, before spending three days exploring the cave below alone to a depth of 700 m.

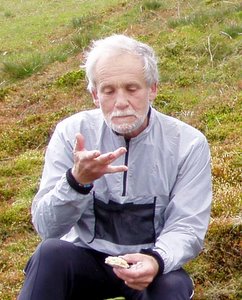

One can go on for a long time listing Mike's many achievements, but for us who were fortunate to know him, it will be Mike himself and his friendship that will be remembered best. He was a quiet, modest, and thoughtful man who charmed all that he met, and who had the knack of making everybody think that they were special. He listened first, and spoke second; and was generous with his knowledge, his time, and his possessions. He will be sadly missed by many people, but his legend will live on.

Mike's funeral was attended by the Great and Good of the caving world, and his ashes were subsequently scattered at Gaping Gill by his daughter Hazel, his sister Mary, and the author. A memorial plaque may be found discretely tucked away in a corner of Meregill Skit.